[Old] Rapid Laboratory Particle Size Analysis of Cements Using Laser Diffraction

2021-08-05Application Note

Optimize cement milling efficiency and save costs with the Bettersizer 2600. This rapid, user-friendly laser diffraction system ensures consistent, repeatable fineness analysis against ideal parameters for all cement grades, confirming product specifications.

| Product | Bettersizer 2600 |

| Industry | Building Materials |

| Sample | Cement |

| Measurement Type | Particle Size |

| Measurement Technology | Laser Diffraction |

Jump to a section:

Abstract

The laser diffraction method for measuring particle size was first invented commercially in 1974 and the first industries to use the technique were coal, ceramics, chocolate and cement.

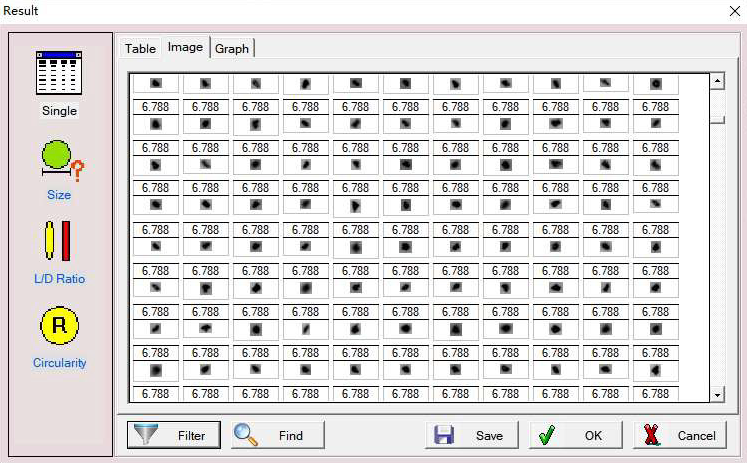

The particle size distribution or fineness of cement has been measured by laser diffraction in laboratories since 1975. Why was the cement industry such an early adopter? The answer lies in the fact that the particle size distribution of cement directly affects the hardening rate, strength and fluidity of the final set concrete – the major user of cement. Producing the cement to make the concrete is a costly business and accurate and repeatable measurement of the cement particle size is an absolute necessity to reduce costs and provide an optimized distribution. The Bettersizer 2600 laser diffraction system is widely used in the cement sector to provide the information QC and laboratory managers need to help reduce these costs but remain in specification. In addition, as shown in Figure 1, a new generation of particle size analyser is now able to measure both the size and shape of cement which will open up new research areas on not just optimal size but also optimal shape.

Introduction

The most common cement is ordinary Portland cement (OPC) which is a grey powder, but there are other types produced for different applications. Broadly speaking cement is produced by a 3-stage process that involves initial raw milling of the limestone in a primary crusher where the rocks are ground down to the size of baseballs followed by a secondary crusher which grinds them down to 2cm in size.

The second stage (clinkering) involves the mixing of this ground material, Silica, Iron ore, Fly ash and sometimes Alumina shale being treated in a preheater where the temperature increases from 80 to 800 degrees C. At this temperature the mix is calcined thus removing the CO2. The feed is sent to a roller mill where the dry Raw Meal is created and transported to the Rotary kiln. All the ingredients are heated up to a temperature of 1450-1550 degrees C at which a chemical reaction can take place driving off certain elements in gaseous form. The remaining elements form a grey material called the clinker. A balance has to be maintained between insufficient heat which results in under burnt clinker containing unconverted lime and excessive heat which shortens the lifetime of the refractory bricks in the kiln.

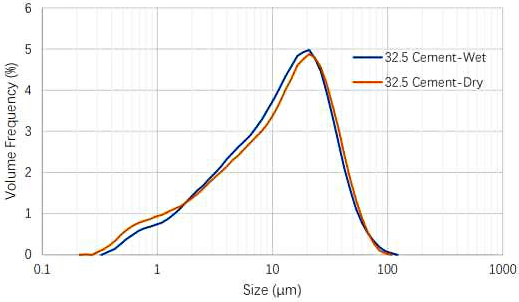

| Sample Name | D10 (µm) | D50 (µm) | D90 (µm) |

| 32.5 Cement - Wet | 1.912 | 11.41 | 32.56 |

| 32.5 Cement - Dry | 1.525 | 11.57 | 33.85 |

Finally, the clinker is ground after cooling to produce a cement fineness of less than 45 microns. Gypsum is blended with the ground clinker to control the cement hydration rate such that its setting time is appropriate for the application. Significant amounts of electrical energy are required for milling and the total power demand depends on the fineness of the grind, the distribution of particle size, and the efficiency of separation of the finely ground particles. The finer the grind, the more reactive the finished cement is and in turn the faster its setting time. Rapid-setting cements will thus have a smaller particle size than cements that have lower reactivity and low hydration heat. As a general rule reducing the particle size increases rate of hydration and strength.

Many historical techniques have been used to measure the particle size/fineness of the cement. The first were 45-micron sieves which only provide the second largest dimension, Blaine air permeability which predicted the compressive strength by a single number and Wagner turbidimeter. These techniques took a minimum of 5 minutes of measurement time and were limited to only providing a single number. Laser diffraction however became the instrument of choice in the 1990s because the technique is easy and reproducible and in addition is much faster than older methods. In addition, it calculates many more relevant parameters with which to optimize the cement particle size distribution.

There are a number of cement types, but we will focus on grades 32.5, 42.5 and 52.5 which are named after the expected strength derived from each of their optimized particle size distribution/fineness. The Bettersizer 2600 can measure the fineness of cement in its natural dry state or as a wet dispersion using and industrial alcohol such as Propanol or Ethanol. As can be seen in Figure 2, both wet and dry dispersion methods yield the same result but due to lower running costs, better statistical representation and easier usage, the dry method is preferred. When making a wet analysis of cement up to 5 different parameters need to be taken account including solvent used, pump speed, need of ultrasound, the ultrasonic dispersion time and strength of ultrasound. When using the dry analysis method there is only one requirement and that is to make a pressure titration curve. This involves measuring the cement at 4 different pressures typically from 1-4 Bar.

Experimental

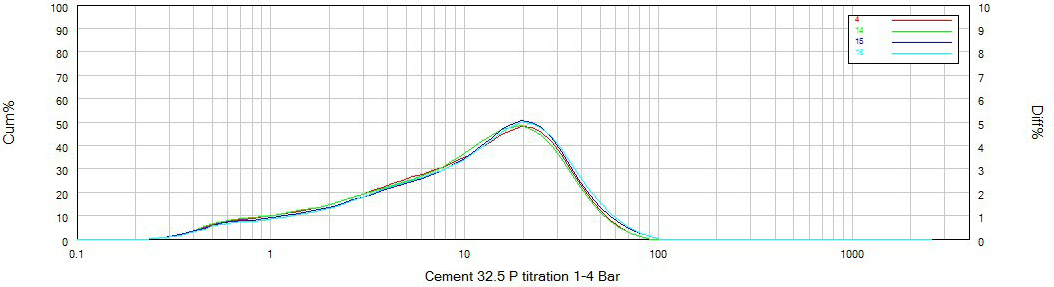

| Sample Name | D06 (μm) | D10 (μm) | D16 (μm) | D25 (μm) | D50 (μm) | D75 (μm) | D84 (μm) | D90 (μm) | D97 (μm) |

|

32.5 Cement – 1 bar

|

1.065 | 1.692 | 2.803 | 4.706 | 12.47 | 23.45 | 29.60 | 35.78 | 51.63 |

|

32.5 Cement – 2 bar

|

1.002 | 1.579 | 2.624 | 4.509 | 12.18 | 22.78 | 28.58 | 34.54 | 50.06 |

|

32.5 Cement – 3 bar

|

0.950 | 1.465 | 2.410 | 4.107 | 11.17 | 21.80 | 27.51 | 33.25 | 46.92 |

|

32.5 Cement – 4 bar

|

0.935 | 1.438 | 2.368 | 4.089 | 11.13 | 21.24 | 26.88 | 32.5 | 46.00 |

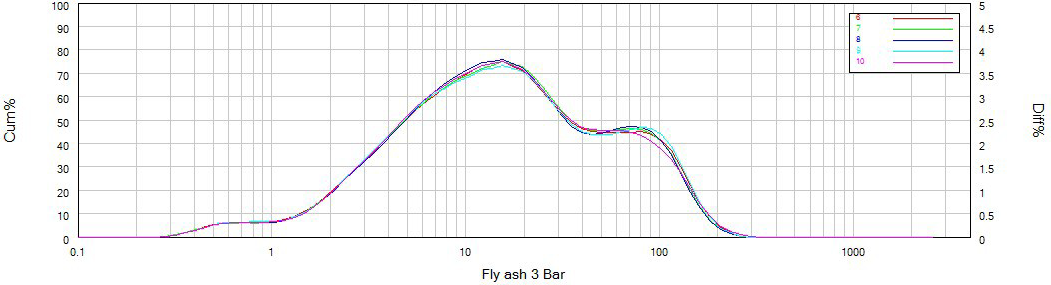

For many applications in other industries results can change at different pressures but as we can see in Figure 3 the variation between results at 4 different pressures is minimal.

Typically, a pressure of 3 bar is recommended for dispersion in conjunction with a vacuum to suck away the dispersed particles after they have exited the measuring cell.

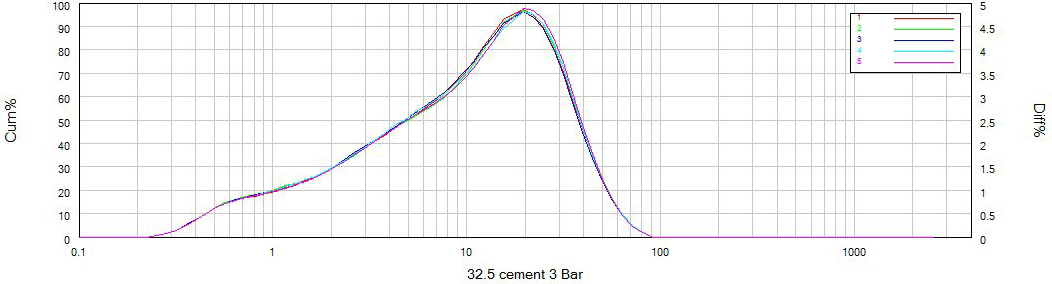

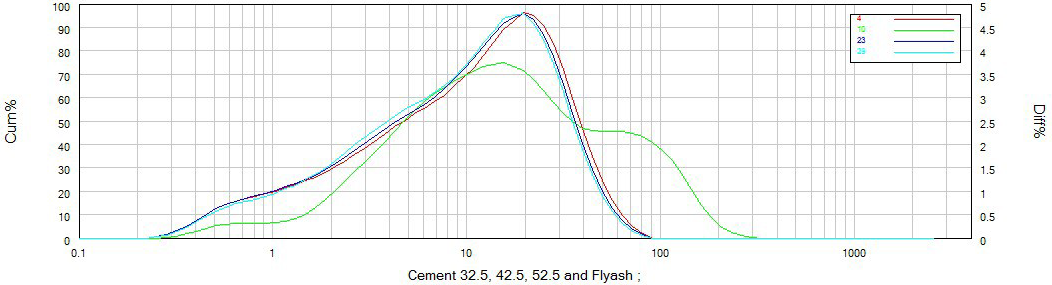

In order to make a measurement a sample of cement is placed on the dry sample feeder, as can be seen in Figure 4. An icon on the computer screen is activated by the mouse which performs a fully automated measurement and analysis of any number of repeat results, in this case 5 repeat analyses were attained in less than 90 seconds (Figure 5). In addition to the measurement of cement, it is also possible to measure additives such as fly ash (Figure 6). Comparison graphs of measurements from 3 grades of cement (32.5, 42.5 and 52.5) and the fly ash can be made(Figure 7).

| Sample Name | D06 (μm) | D10 (μm) | D16 (μm) | D25 (μm) | D50 (μm) | D75 (μm) | D84 (μm) | D90 (μm) | D97 (μm) |

|

32.5 Cement – 3 bar - 1

|

0.958 | 1.488 | 2.450 | 4.180 | 11.29 | 21.60 | 27.33 | 33.13 | 46.91 |

|

32.5 Cement – 3 bar - 2

|

0.942 | 1.450 | 2.402 | 4.123 | 11.34 | 21.80 | 27.55 | 33.32 | 46.82 |

|

32.5 Cement – 3 bar - 3

|

0.946 | 1.461 | 2.400 | 4.090 | 11.05 | 21.40 | 27.08 | 32.76 | 46.42 |

|

32.5 Cement – 3 bar - 4

|

0.950 | 1.465 | 2.410 | 4.107 | 11.17 | 21.80 | 27.51 | 33.25 | 46.92 |

|

32.5 Cement – 3 bar - 5

|

0.955 | 1.482 | 2.451 | 4.179* | 11.44 | 21.11 | 27.74 | 33.42 | 46.65 |

|

Repeatability

|

0.68% | 1.06% | 1.06% | 1.01% | 1.35% | 1.22% | 0.91% | 0.77% | 0.45% |

| Sample Name | D06 (μm) | D10 (μm) | D16 (μm) | D25 (μm) | D50 (μm) | D75 (μm) | D84 (μm) | D90 (μm) | D97 (μm) |

|

Fly Ash – 3 bar - 6

|

2.077 | 2.976 | 4.293 | 6.439 | 15.18 | 39.24 | 62.89 | 86.20 | 132.0 |

|

Fly Ash – 3 bar - 7

|

2.132 | 3.026 | 4.340 | 6.480 | 15.33 | 38.82 | 61.78 | 83.78 | 128.3 |

|

Fly Ash – 3 bar - 8

|

2.135 | 3.041 | 4.371 | 6.510 | 15.06 | 38.57 | 62.05 | 82.63 | 127.6 |

|

Fly Ash – 3 bar - 9

|

2.098 | 2.992 | 4.285 | 6.385 | 15.29 | 39.95 | 64.77 | 87.97 | 132.3 |

|

Fly Ash – 3 bar - 10

|

2.123 | 3.017 | 4.317 | 6.414 | 15.04 | 38.17 | 60.57 | 83.10 | 132.0 |

|

Repeatability

|

1.18% | 0.87% | 0.81% | 0.78% | 0.86% | 1.75% | 2.50% | 2.44% | 1.76% |

| Sample Name | D06 (μm) | D10 (μm) | D16 (μm) | D25 (μm) | D50 (μm) | D75 (μm) | D84 (μm) | D90 (μm) | D97 (μm) |

|

32.5 Cement – 3 bar - 4

|

0.950 | 1.465 | 2.410 | 4.107 | 11.17 | 21.8 | 27.51 | 33.25 | 46.92 |

|

32.5 Cement – 3 bar - 23

|

0.948 | 1.454 | 2.356 | 3.955 | 10.57 | 20.60 | 26.03 | 31.28 | 44.44 |

|

32.5 Cement – 3 bar -29

|

1.006 | 1.543 | 2.429 | 3.941 | 10.29 | 19.98 | 25.23 | 30.45 | 43.14 |

|

Fly Ash – 3 bar - 10

|

2.123 | 3.017 | 4.317 | 6.414 | 15.04 | 38.17 | 60.57 | 83.10 | 132.0 |

The results from all these experiments can be displayed in tabular, graphical, percentage or Tromp (Efficiency of separation) curve form but the most important value within the cement industry is the percentage of ground cement that is between 3 and 32 microns.

Theoretically this percentage should approach 70% in order to have the optimal strength properties. The rationale for this percentage is because particles larger than 45 microns aren’t fully hydrated and an excess of particles smaller than 3 microns cause faster exothermal setting in the final product due to the increased heat of hydration. Increased amounts of gypsum can be added to inhibit this increased heat of hydration and thus control the setting time when water is added to the cement. The addition of gypsum can be an unnecessary cost particularly if the grinding process is optimized to produce a cement which has 70% of the particles by volume lying between 3 and 32 microns.

From a research perspective, you can measure alternative additives and check the effect on the overall size distribution and determine how much to add to reach the optimal strength. Therefore, with the Bettersizer 2600, you have a tool that is fast easy to use, acts in a QC capacity or as a research tool when working with new additives/raw materials. In a relatively recent advance, the ability of the Bettersizer S3 Plus to measure shape as well as size provides extra advantages.

We have already seen that a cement particle size is now seen as critical for the determination of the quality of the cement. Finer particle sizes have a greater surface area affecting the cement’s compressive strength and setting rate.

However, the cement particles’ shape also has an influence as spherical particles will have a lower surface area than cement that is irregular in shape if both populations have nominally the same size. The required amount of water in a cement mix will reduce for spherically shaped cement and increase as the particles become more irregular in shape.

Conclusions

The large power demands of finish milling mean that improved monitoring of the grinding efficiency and optimization of the classifier speed yields an in- specification product with significant energy efficiency improvements and ultimately cost savings. This is best achieved by having a laser diffraction which is quick and easy to use with consistent repeatable results being attained no matter which operator is using the system.

In addition, by having control of standard results for each cement grade maintained inside the computer database, all newly produced cement for all grades can be compared in seconds to the ideal products fineness parameters. With the added software benefit of being able to put upper and lower set point limits on each key parameter, the operator will know when the latest grind meets the specifications for that grade of cement. The Bettersizer 2600 has all this functionality in its software and provides the rapid laboratory fineness analysis to prove the cement meets the specifications and is thus fit for purpose. New feed materials and additives are being introduced all the time with different morphologies and from different sources. The Bettersizer S3 Plus is a future-proof laser particle size analyzer which is an integrated laser diffraction and dynamic image analysis system providing the latest in added versatility and adaptability to meet these new challenges by measuring not only the particle size but also the shape of these novel materials. It is already matching the increasing demands from industries that are now seeing the increasing importance of shape as well as size in the improvement and economics of their products.

About the Author

|

Zhibin Guo Application Manager @ Application Research Lab, Bettersize Instruments |

Recommended articles

Rate this article