Particle Size Distribution Control in Metal Mining: From Ore Liberation to Downstream Processing

2026-02-17Application Note

Abstract: Particle size distribution (PSD) is a decision-critical variable in metal mining, directly influencing comminution efficiency, mineral liberation, recovery performance, and tailings behavior. This application note demonstrates why single parameters such as P80 are insufficient and shows how full PSD characterization, combining laser diffraction and sieving, supports effective process control from grinding to downstream processing.

Keywords: Particle size distribution (PSD), Metal mining, Mineral processing, Grinding and classification, Flotation and leaching, Tailings management, Laser diffraction, Sieve analysis

| Product | Bettersizer 2600 Plus |

| Industry | |

| Sample | Metal ores, mineral slurries, and tailings materials |

| Measurement Type | Particle Size |

| Measurement Technology |

Introduction

In metal mining and mineral processing, particle size is a key physical parameter that links energy consumption, metallurgical performance, and downstream operational stability. As ore grades decline and processing routes become increasingly complex, accurate characterization of particle size distribution (PSD) has become essential for effective process control.

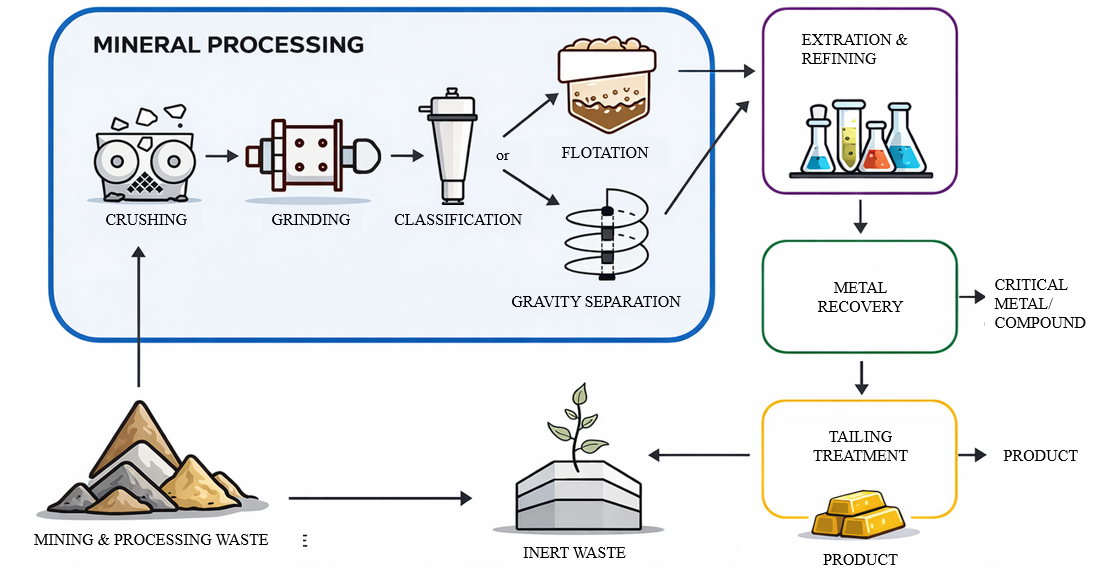

Beyond its traditional role as a laboratory measurement, particle size now functions as a decision-critical variable influencing every major processing stage including grinding and classification, flotation, extraction and refining, and tailings management.[1] Upstream PSD choices directly affect recovery efficiency, reagent and water usage, and long-term operational risk.

This application note highlights the operational importance of PSD in metal mining and demonstrates how PSD measurements inform practical engineering decisions across the key stages of mineral processing.

Figure 1The breakdown of the mineral processing steps within the mining chain

PSD Considerations Across Key Processing Stages

PSD influences each stage of mineral processing in different ways, with each stage being sensitive to specific size ranges. Understanding which part of the PSD matters most at each stop is essential for effective control and risk reduction.

Table 1. Summary of the key PSD control objectives, critical particle size regions, and major operational consequences across metal mining process stages.

| Stage | What PSD Controls | Particle Size Focus | Primary Consequence |

| Grinding & Classification | Degree of mineral liberation and circuit stability | P80 and PSD shape | Determines energy efficiency and governs downstream performance |

| Flotation | Recovery efficiency and selectivity | Size-by-size recovery behavior |

Identifies where material losses occur in the circuit |

| Extraction & Refining | Reaction kinetics and extraction efficiency | Fine fraction (surface-area dependent) |

Impacts residence time and consumables demand |

| Tailings Management | Settling behavior and water recovery | Fine end of the PSD | Governs dewatering performance and metal mobility risk |

Data-Driven Discussion: PSD as a Process Control Tool

Grinding and Classification: Similar P80, Different Outcomes

In grinding circuits, P80, the size at which 80% of the material is finer, is commonly used as a practical control metric for tracking particle size reduction. Figure 2 shows the P80 change generated under different grinding conditons. PSD curves generated under different grinding conditions. As grinding time increases, particle size decreases predictably. As a result P80 provides a practical operational parameter for comparing grinding conditions and adjusting variables such as grinding time, power input, and overall milling strategy to reach a targeted size.[2]

Figure 2. Relationship between grinding time and P80 at varying grinding rates

Table 2. Combined sieve and laser scattering descriptors for the seven slurry PSDs

| PSD | P38 (Sieve, %) |

P53 (Sieve, %) |

P212 (Sieve, %) |

P300 (Sieve, %) |

D10 (LD, µm) |

D50 (LD, µm) |

D80 (LD, µm) |

| PSD 1 | 59.0 | 71.3 | 93.9 | 100.0 | 1.85 | 14.60 | 75.87 |

| PSD 2 | 59.0 | 71.3 | 93.9 | 100.0 | 1.86 | 29.59 | 96.96 |

| PSD 3 | 49.8 | 70.4 | 93.9 | 100.0 | 2.23 | 39.21 | 90.49 |

| PSD 4 | 39.0 | 65.0 | 92.8 | 100.0 | 2.50 | 44.41 | 91.37 |

| PSD 5 | 48.5 | 59.0 | 83.8 | 98.9 | 3.11 | 50.17 | 143.80 |

| PSD 6 | 28.9 | 49.8 | 85.5 | 97.8 | 6.17 | 65.99 | 148.70 |

| PSD 7 | 10.0 | 39.0 | 83.0 | 96.5 | 29.02 | 82.40 | 155.60 |

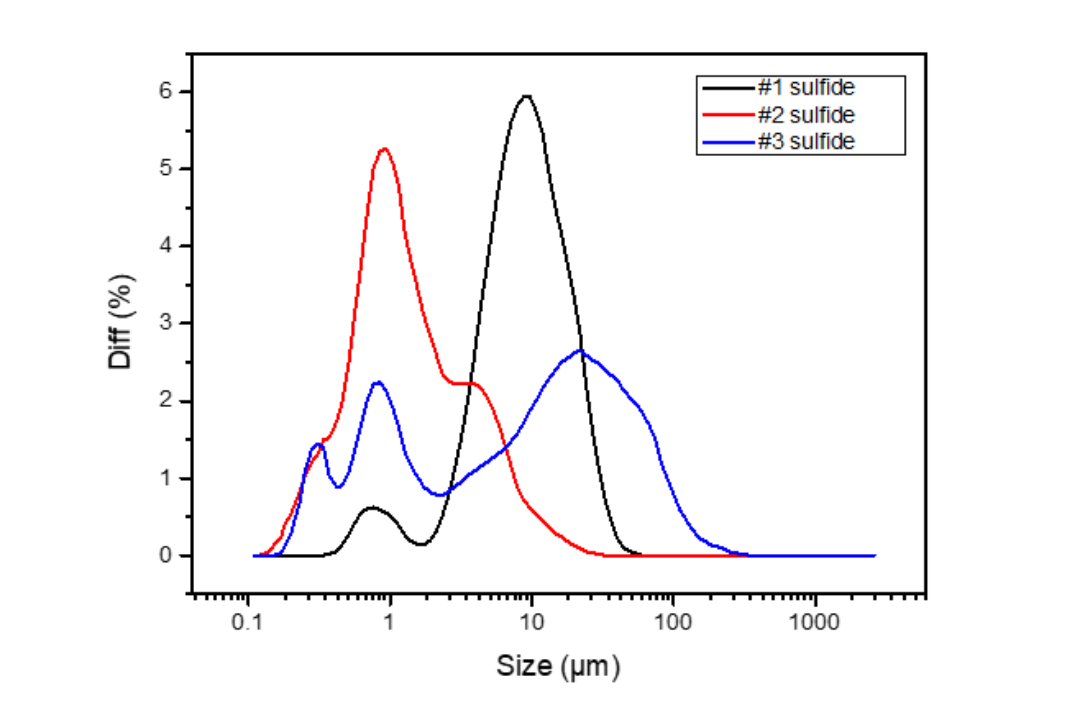

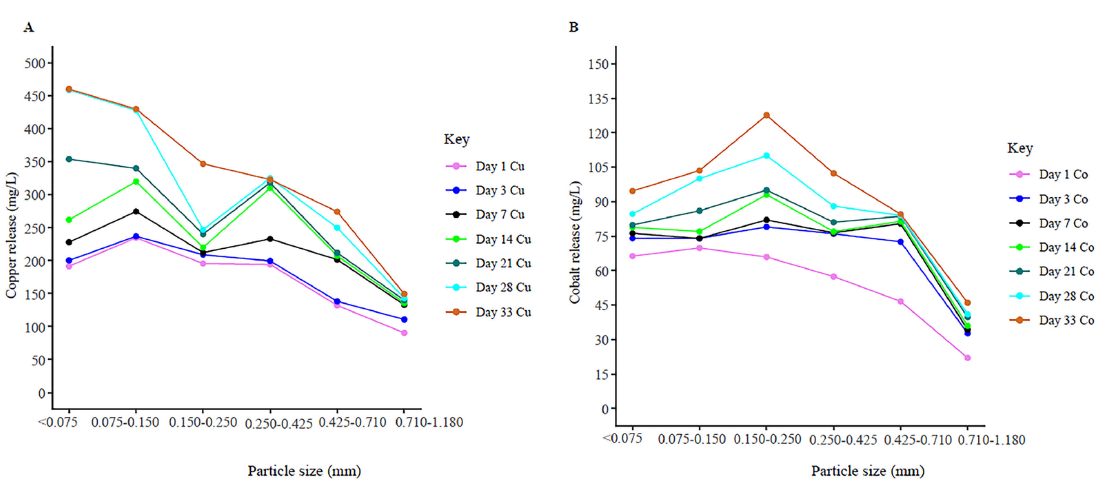

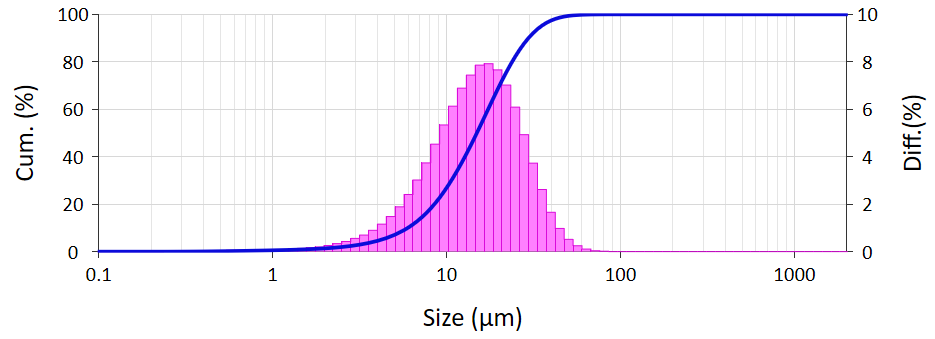

However, P80 alone does not fully describe the resulting particle size distribution. As shown in Table 2, sieve based measurements (e.g., P38, P53)—provide only coarse resolution and cannot capture fine particle behavior or describe complex PSD features.[3] In contrast, laser diffraction (LD) analysis enables full PSD characterization, providing detailed insight into the fine fractions and revealing multimodal or skewed distribution shapes as shown in Figure 3. The combined results show that although samples PSD5–PSD7 exhibit similar P80 values, they differ substantially in D10 and D50, reflecting significant variation in fines generation and overall distribution shape despite comparable P80 values. These differences highlight why full PSD characterization is necessary for effective grinding-circuit control.

Figure 3. PSD curves of seven slurry samples obtained using the laser diffraction method.

Flotation: Size-Dependent Losses Across Process Streams

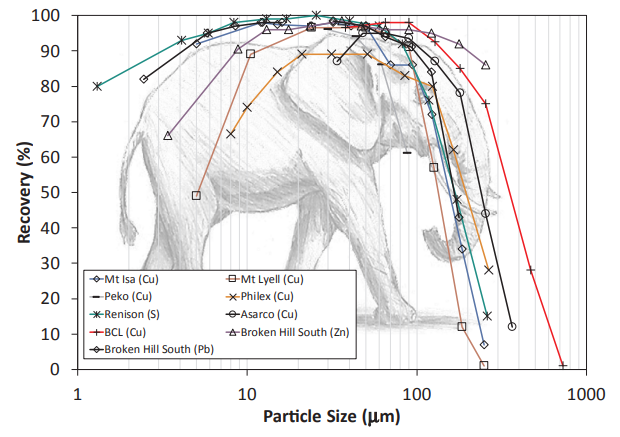

In conventional sulfide flotation systems, the relationship between particle size and recovery is commonly illustrated by the well-known “elephant curve”, as shown in Figure 4. This characteristic trend, higher recovery at intermediate particles sizes and lower recovery at both the fine and coarse ends, has remained largely unchanged over decades of industrial practice.[4]

Recovery losses in the fine fraction typically arise from reduced selectivity, driven by mechanisms such as entrainment and slime coating. At the coarse end, losses occur due to incomplete liberation, reduced collision efficiency and turbulence-driven detachment from bubbles. Because these behaviors vary strongly with particle size, a single size metric is insufficient for characterizing flotation performance.

A full PSD, combined with size-by-size mineral and recovery data, is required to accurately pinpoint where losses occur across the process streams and to interpret the true flotation response.

Figure 4. Conventional flotation data for industrial sulfide flotation circuits.

Extraction and Refining: PSD Effects on Reaction Kinetics

In hydrometallurgical extraction, smaller particles generally leach faster due to their higher specific surface area and shorter mass-transfer diffusion paths. However, work by Gbor and Jia demonstrates that PSD, not just the mean particle size, plays a critical role in determining leaching behavior.[5]

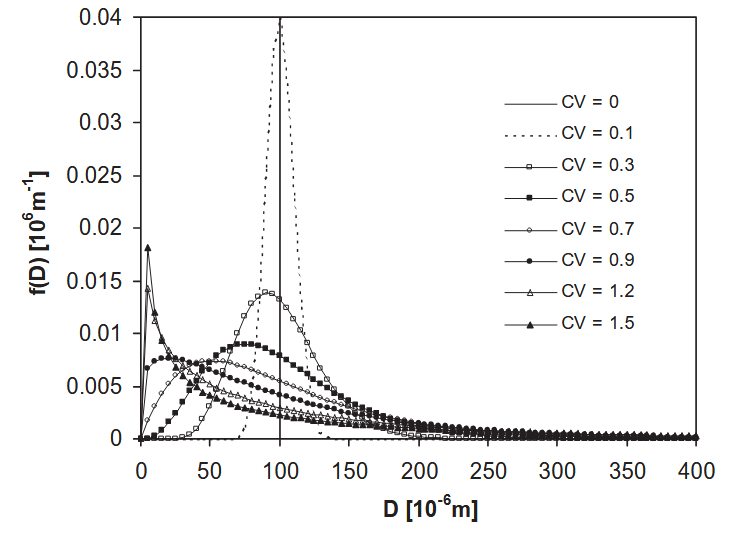

As illustrated in Figure 5, increasing the Coefficient of Variation (CV) broadens the PSD, producing a higher proportion of fine particles while also extending the coarse-particle tail. The corresponding leaching curves in Figure 5 display a clear two-stage behavior:

- Fine particles contribute to rapid initial conversion due to their large reactive surface areas

- Coarse particles dominate the slower, late-stage reaction tail because of their longer diffusion paths and reduced accessible surface area.

When the PSD is narrow (i.e. low CV) these distribution effects are minimal, and the particle population can be treated as effectively uniform. However, for wide distributions (typically reported as CV > 0.3), PSD must be explicitly considered to accurately calculate leaching rates, interpret kinetic parameters, and compare process conditions across samples or circuits.

Figure 5. Particle size distributions at varying CV values and fraction reacted curves as a function of time.

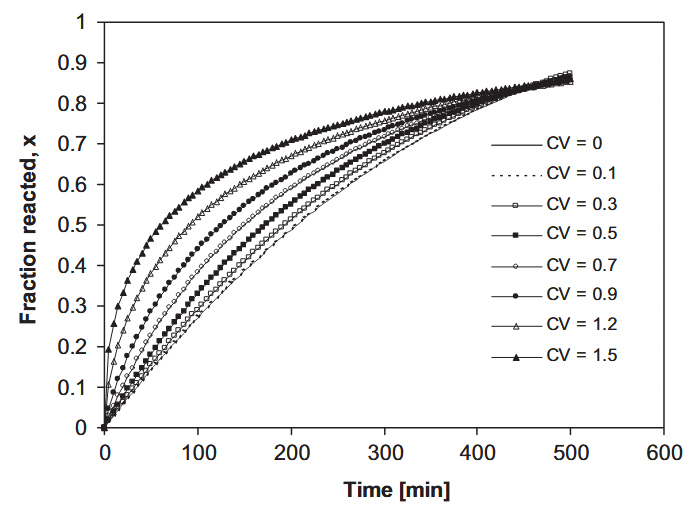

Tailings Management: Particle Size Effect on Metal Release

Particle size is a critical factor in assessing and managing the environmental risk associated with tailings storage. Fine particles consistently exhibit higher metal release, whereas coarse fractions generally show significantly lower release rates As illustrated in Figure 6, both Cu and Co release display a stronge size dependency: fine fractions release substantially more metal, while coarser fractions release markedly less. This trend indicates that the environmental behaviour of tailings, particularly metal mobility and leaching risk, is largely governed by the fine end of the PSD.[6]

Figure 6. Size-dependent Cu (A) and Co (B) release from slag material

Laser Diffraction Method in Mining Applications

Mining materials present specific challenges for particle size analysis, including wide size distributions, irregular par ticle shapes, and high material densit y. Laser diffraction (LD) has become a widely adopted technique in mining because of its broad measurement range, rapid analysis speed, and strong repeatability. International standards such as ISO 13320 and ASTM B822 provide established guidelines for conducting and reporting laser diffraction-based particle size measurements.

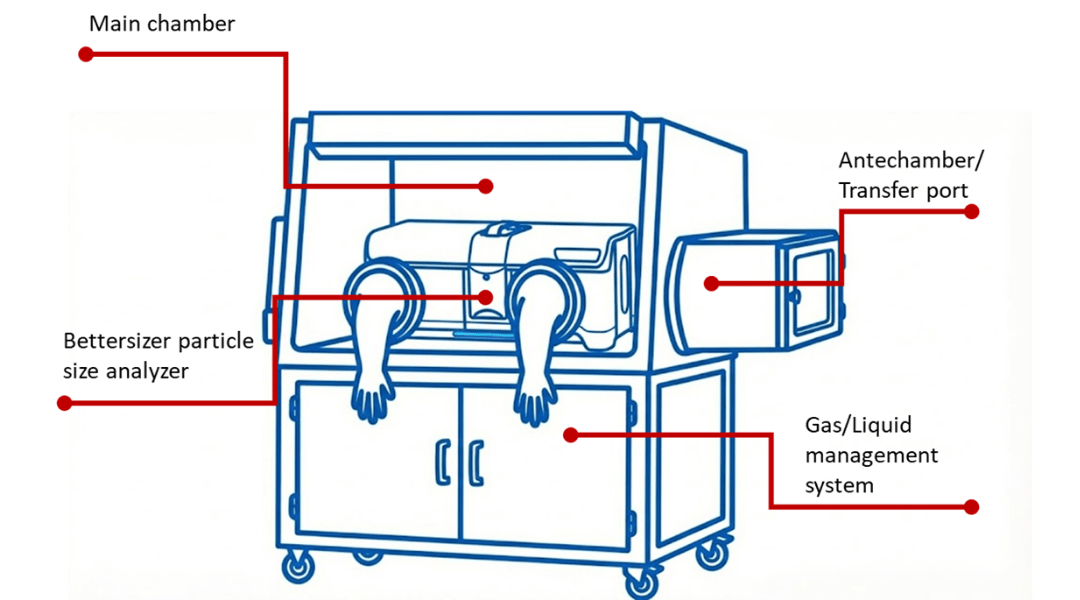

The Bettersizer 2600 Plus particle size analyzer from Bettersize is designed to meet the demands of mining environments, delivering reliable PSD data for routine quality control, process monitoring, and application development.

The Bettersizer 2600 Plus provides detailed and flexible PSD analysis, including:

- Wide measurement range: 0.02–3500 μm, covering both fine and coarse fractions commonly encountered in mining processing applications.

- Common size parameters: D10, D50, D80, D90 and other characteristic values used in mining and plant operations.

- Distribution width indicators: Metrics such as Span for quantitative comparison of PSD broadness or narrowness.

- Flexible reporting formats: Log-normal PSD tables, cumulative pe rce ntage report, and sieving - style distribution reports for easy interpretation across different teams.

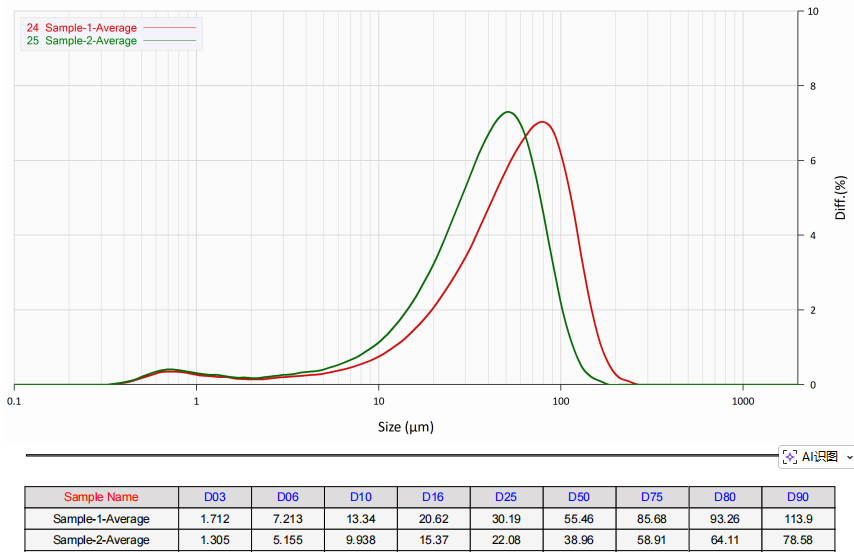

For example, PSD measurements of a manganese ore under varying product conditions can be reported using D80, Span, and multiple distribution formats, enabling rapid comparison of product specifications.

Figure 7. PSD curve of manganese powders

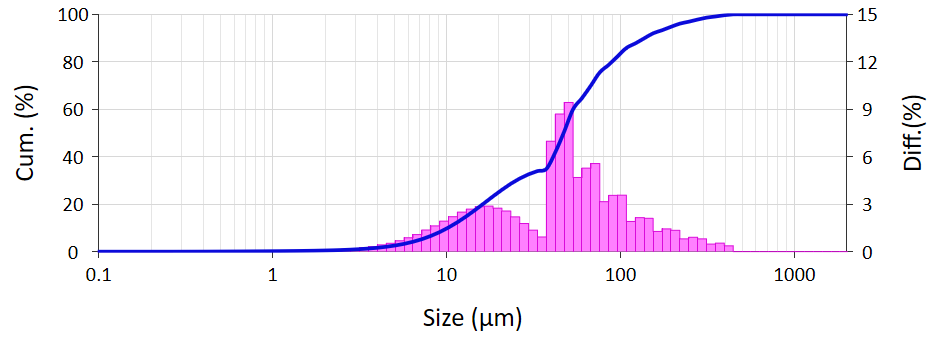

In practical mining workflows, sieve analysis remains standard method, particularly for characterizing coarse fractions due to its simplicity and established used among test engineers. To maintain these existing practices while improving fine-end resolution, laser diffraction and sieve results can be integrated into a combined measurement framework.

As illustrated in the iron ore sample (Table 3 and Figure 8), coarse material is quantifiedvia sieving, while fine particles are measured using laser diffraction. This combined approach preserves traditional measurement methods while significantly enhancing resolution in the fine size range, enabling a broader and more comprehensive particle size distribution suitable for process control and product quality management.

Table 3. Sieve data for the iron ore sample

| Size (μm) | Mass in fraction (kg) |

| <38 | 1.090 |

| 38-53 | 0.707 |

| 53-75 | 0.442 |

| 75-106 | 0.295 |

| 106-150 | 0.177 |

| 150-212 | 0.118 |

| 212-300 | 0.074 |

| 300-425 | 0.044 |

Figure 8. (a) Fine particles PSD by laser diffraction, (b) Combined laser diffraction and sieving results.

Conclusions

Across the mineral processing flowsheet, particle size decisions made during grinding largely define downstream recovery performance, operational stability, and tailingsrelated evironmental risk. Treating particle size distribution as a controllable process variable—rather than a single descriptive measurement—provides mining operations with a practical, cost-effective lever for improving performance without requiring major changes to the existing flowsheet.

Reference

[1] Whitworth, A. J.; Forbes, E.; Verster, I.; Jokovic, V.; Awatey, B.; Parbhakar-Fox, A. Review on advances in mineral processing technologies suitable for critical metal recovery from mining and processing wastes, Cleaner Eng. Technol. 2022, 7, 100451.

[2] Elbendari, Abdalla M. Ibrahim, Suzan S., 2025. Optimizing key parameters for grinding energy efficiency and modeling of particle size distribution in a stirred ball mill, Scientific Reports (2025) 15: 3374

[3] Grabsch, A.F., Yahyaei, M., Fawell, P.D., 2020. Number-sensitive particle size measurements for monitoring flocculation responses to different grinding conditions. Minerals Engineering 145 (2020): 106088

[4] Lynch A, Johnson N., Manlapaig E. and Thorne C. (1981). Mineral and Coal Flotation Circuits: Their Simulation and Control. Elsevier Publishing, Amsterdam, 291 pp.

[5] Gbor, P.K. and Jia, C.Q. (2004). Critical evaluation of coupling particle size distribution with the shrinking core model. Chem. Eng. Sci. 59: 1979–1987.

[6] Hariman, J., Makangila, M., Mundike, J., Maseka, K., Effect of particle size, pH, and residence time on mobility of copper and cobalt from copper slag. Scientific African, 23(2024) e02117

About the Authors

|

Perfil Liu |

Recommended articles

Rate this article